Albert John Smith

Gunner 200450 Albert John Smith, 3rd Battalion, Tank Corps

Albert, known as Jack, was born in Andover on 13 September 1894. His parents, Albert Bernard and Julia (née Bradford) Smith, had moved there from their native Dorset in 1891, presumably because Jack found better employment. In 1906 they moved again, this time to Newbury. Albert senior was a compositor by trade, putting together the text and images in preparation for printing. When working in Newbury it was as an overseer for a group of compositors.

The couple had a total of eight children: David Percy (born 1888) and Hilda Amelia (1890) were born in Dorchester; Beatrice May (1893), Jack, Elise Maud (1898), Emma Julia (1901) and Reginald Bernard (1905) in Andover. Jack and many of his siblings began their education at Miss Gale’s Infant School in Andover which took children from the age of three to seven after which the children would probably have gone to the Andover National School (now Andover Primary School) though, as nonconformists the Smith’s may have preferred another option.

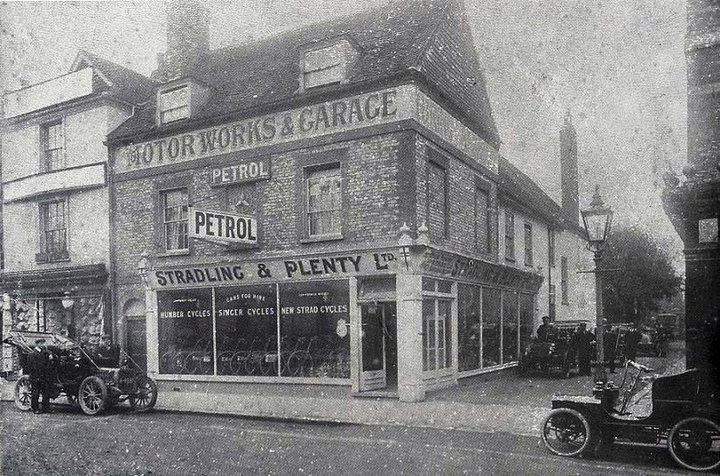

A rather poor image of Stradling & Plenty's motor works and garage in Northbrook Street. Jack learned his skills as a motor-cycle mechanic here. |

When war broke out it did not take long for Jack to volunteer; he signed up on 31 August 1914 joining the local infantry – the Royal Berkshire Regiment (No 11291). In the opening months of the war the Army rapidly realised that it had underestimated the power of the machine gun and that mobile forces were very useful in harrying the enemy and rapidly plugging gaps in the line – this was before the war settled down into trench warfare and when an irregular force of armoured cars operated by the Navy in Belgium was proving very effective in disrupting German attempts to outflank the French and British forces. In October 1914 the War Office sanctioned the establishment of a Motor Machine Gun Service (MMGS) and called upon experienced motorcyclists to enlist – such experience being more valuable than military training at that time.

Newbury Weekly News, 10 June 1915 – Local War Notes

The Roll of Honour displayed in Messrs Stradling and Plenty’s window, Northbrook-street, is striking evidence of the contribution made by one firm to the King’s Forces. No less than 25 members of the staff have gone on active service since the outbreak of war. They are as follows:- Sergt W Winter, DCM, 1st Royal Berks (wounded); Sergt N Stradling, Berks Yeomanry; Corpl A Rogers, Privates H Hall, H King, G Gregory, H White, F Stacey, W Whatmore, P Challis, H Street, H Mealin, N Theaker, W Murray, W Dibsdale, R Butler, E Hill, F Mitchell, ASC(Mechanical Transport); Farrier W Minns, ASC attached to RFA; Driver G Edwards, Anti-Aircraft Corp; Driver H Carter, French Red Cross; Privates J Smith, Machine Gun Section; E Franklin, Royal Berks; P Matthews, Royal Berks; E Hamblin.

A battery of the Motor Machine Gun Service. |

Jack must have volunteered for this new force and, unlike many early recruits trying to make the same move, was evidently released by his regiment. Thus he joined the MMGS, which, as it had been created as an arm of the Royal Artillery, meant he assumed the rank of Gunner, No 437. The rank did not mean that he was the man in the sidecar with the machine gun, it is almost certain that he was the driver/mechanic.

By the time the new service was operational its time was all but past; the two opposing lines had reached the sea and were digging ever deeper as the trench lines took form. Nevertheless units (batteries) of the MMGS were attached to each Division in France and Flanders. Jack landed in France on 10 May 1915 to join the 10th Battery MMGS in the 9th Division. If he saw action during his time with the battery it was more likely to be as part of a machine gun section in the line than on a motorcycle. He described one such action in a letter home:

Newbury Weekly News, 7 October 1915, Local War Notes

Gunner A J Smith, of the 10th Battery Motor Machine Gun, writing to his parents in Berkeley-road, describes a narrow escape he experienced. He had been engaged in continuous firing in preparation for the advance, and about daybreak left his gun to go and make some tea for the lads. He was away ten minutes, and on returning, found that a German bullet had struck the gun, putting it out of action. Probably that cup of tea saved the gunner’s life, but he was very much annoyed that his gun was silent just when most wanted. However, he helped to serve the companion gun, which did good service at a critical moment. He tells the story of a wounded Scotchman, who was making his way wearily with his bag-pipes under his arm. “Well Jock, you stuck to your pipes then,” “Eh, mon, I have lost my rifle, my equipment, everything else, but I’d sooner be blown to pieces than let the Germans have my pipes for a souvenir.

In June 1916 the battery was detached from the division and returned to the UK where the personnel became a part of the Heavy Section Machine Gun Corps at Elveden Camp in Suffolk. This was a move from the Royal Artillery to the Machine Gun Corps, so Jack ceased to be Gunner Smith and became Private Smith again, however, his number was retained with a qualifier added to make it 437 MGC(M).

Here Jack had to learn new driving skills because this was the nascent Tank Corps, testing and preparing the Mk I Tanks to go to war. Jack was not among the first tank crews to go into battle at Flers on 15 September 1916, but the odds are that he took part in other tank actions, notably the massive tank assault at Cambrai in November 1917. When the Heavy Section became the new Tank Corps on 27 July 1917 it was formed into battalions; Jack served in the 3rd Battalion, which, in early 1918 became one of the first to be equipped with the new medium tank – officially Tank, Medium Mark A, but best known as the Whippet. The change to the Tank Corps also meant a change of regimental number to 200450.

Whippet tanks from the 3rd Battalion at Mailly Maillet on 26 March 1918. |

Whippets of the 3rd Battalion (renamed the 3rd Light Tank Battalion) were the first to go into action during the German spring offensive on 26 March 1918. Whippets came into their own in the fluid fighting dashing to and fro doing their best to stem the German tide, but there were far too few of them to make a major impact.

Tanks in the Great War 1914-1918, John Fuller

March 26 is an interesting date in the history of the Tank Corps, for, on the afternoon of this day, the Whippet Tanks made their debut. Twelve of these machines, belonging to the 3rd Tank Battalion, moving northwards from Bray were ordered to advance through the village of Colincamps to clear up the situation, which was very obscure. About 300 of the enemy were met with advancing on the village in several groups; these were taken completely by surprise, and on seeing the rapidly moving tanks fled in disorder, making no attempt at resistance. The Whippets then patrolled towards Serre and after dispersing several strong enemy patrols withdrew, having suffered no losses in tanks or personnel. This action was particularly opportune, as it cheeked an enveloping movement directed against Hebuterne at a time when there was a gap in our line.

The Germans were stopped at Villers-Bretonneux by Australian, British and French troops in desperate fighting between 30 March and 4 April. The Germans switched their offensive from the Somme north to the Lys and then South to the Aisne before eventually running out of steam.

On 8 August the British struck back at the Battle of Amiens using refined ‘all arms’ tactics to smash through the relatively weak German line first created in April. Artillery, infantry, tanks, aircraft all acting in unison – subtler infantry tactics, technologically advanced detection of enemy artillery, and a massive advantage in men and materiel combined to make the Army that had walked into the machine guns at the Somme and floundered in the mud of Passchendaele into an irresistible force. Weakened by their losses in the Spring Offensive, defending positions that they had not had time to fortify and suffering from loss of morale the Germans had no answer. The breaking of the German line meant that the Whippet came into its own, fast (8½mph) and lethal to infantry, harder for the German artillery to hit than the lumbering Mk V heavy tanks and quicker to reach the enemy artillery and put it out of action.

However, the British did not have it all their way, the Germans did not give way easily; it took a month to push them back 30 miles to the Hindenburg Line, the starting point of their offensive.

Jack went into action on 24 August:

Newbury Weekly News, 26 September 1918 – Local War Notes

Mr and Mrs A B Smith, of 58, Berkeley-road have received sad and mysterious news respecting their son, Gunner A J Smith, Light Tank Corps. On August 24 he went into action; their work was over for the day and they were returning home. When about 800 yards behind the front line a shell struck the tank. Jack and the driver got out to make an examination, when the second shell fell between them. Shortly afterwards the driver was taken away on a stretcher, but the body of “Jack” could nowhere be found, and it remains a mystery whether he is alive or dead. A J Smith joined the Army in September, 1914, and has served 3½ years in France. His first experience of modern warfare was at Loos in 1915, since which he has had his share of work, and this was the fourth time he had gone into action with the tanks.

The mystery was soon solved when his remains were found, presumably having been blown some distance by the shell’s detonation. The War Office was soon able to notify his parents:

Newbury Weekly News, 17 October 1918 – Local War Notes

Mr and Mrs A B Smith, of 58, Berkeley-road, Newbury, have been officially notified by the War Office that their son, Private A J Smith, of the Tank Corps, was either killed in action or died of wounds on or shortly after the 24th August. A message of sympathy from the King and Queen was also forwarded.

Jack was buried in grave XI. D. 17 at Grevillers British Cemetery.

His parents remembered Jack on the anniversary of his death:

Newbury Weekly News, 28 August 1919 – In Memoriam

SMITH – In loving memory of our dear boy, Jack, who fell in France, August 24th, 1918, aged 24 years.

To live in hearts we leave behind, is not to die. – 58, Berkeley Road, Newbury.

Jack's name on Newbury War Memorial. (lower left) |

Locally he is remembered on Tablet 6 of the Newbury Town War Memorial and on the Congregational Church Memorial (now in Newbury Town Hall).

He was also remembered on the memorial window in the Primitive Methodist Chapel in Bartholomew Street (now demolished).

Family

David Percy Smith was the eldest of the Smith children. He chose the Royal Navy as a career enlisting on the 20 April 1903 as a boy sailor, giving his birth date as 9 April 1887 (adding a year to his age). On his 17th birthday he re-enlisted as an adult – the Navy believing that he was 18. When war broke out he was a Leading Seaman serving on the battle cruiser HMS Cochrane, on 1 November 1915 he was promoted to Petty Officer. He was on board HMS Cochrane at the Battle of Jutland in 1916 but transferred to HMS Cullis in February 1917, perhaps looking for a more exciting life. HMS Cullis was a Q-Ship that masqueraded as a merchantman to attract enemy submarines to attack them with gunfire (U boat commanders were reluctant to waste torpedoes on unarmed ships). When the U boat serface the Q Ship would show its true colours and open fire with hidden guns, or simply ram the U boat. HMS Cullis sailed under several names in order to ensure word of its guise did not spread amongst the U boat fleet. The Cullis was sunk by a torpedo (perhaps word had got out) in the Irish Sea on 28 February 1918.

Newbury Weekly News, 21 February 1917 – Local War Notes

Petty Officer D P Smith, of 58, Berkeley-road, was one of the survivors in a disaster which happened recently at sea, and it is satisfactory to learn recently at sea, and it is satisfactory to learn that after knocking about on wreckage for five-and-a-half hourse, he, with others, were picked up by a trawler.

David survived the sinking and was sent to Portsmouth to await a further posting. For his work on the Cullis he was awarded a Distinguished Service Medal:

Newbury Weekly News, 6 September 1917 – Local War Notes

We are pleased to hear that Petty Officer David Percy Smith, son of Mr and Mrs A B Smith, Berkeley Road, Newbury, has been awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for services rendered in action with enemy submarines.

He was in Portsmouth while a plan was being hatched to deny the use of the port of Zeebrugge to enemy shipping, notably U boats. The idea was to sink some old ships to block the harbour and to blow up two explosive laden old submarines alongside a key pier. To support this, a party of Royal Marines would be landed to disable shore defences and cover the naval operations. Lauded as a huge success it had, in reality, little effect on the port.

The SS Iris returns to duty as a Mersey farry after service as HMS Iris on the Zeebrugge raid (and extensive repairs). |

For his efforts David was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (CGM), the citation reads:

P.O. David Percy Smith, O.N. 225904 (Po.). Petty Officer Smith acted as quartermaster of "Iris II.," and carried out his duties with great coolness throughout. On leaving the mole at Zeebrugge, the bridge of his ship was partially shot away, the captain and the navigator being severely wounded. Petty Officer Smith remained at his exposed post under heavy fire, steering the ship to safety with one hand while lighting the compass with a torch held in the other.

The Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. |

Sixteen CGMs were awarded for Naval personnel on the Zeebrugge Raid. After the raid two Victoria Crosses were also awarded by a ballot of the men who took part (two more were awarded in the same manner to marines and four by the conventional means to Naval officers). Traditionally the Navy would award balloted VCs to an officer selected by his fellow officers and an ‘other rank’ selected by his peers. Thus only one VC was available to the ORs, which was awarded to Able Seaman Albert Edward Mackenzie – the results of the ballot have not survived, but one imagines that some of the CGMs were awarded to men who featured strongly.

The French Government also saw fit to award gallantry medals to participants in the raid so David received a Croix de Guerre (equivalent to the British CGM he had already received).

David remained with the Navy well beyond the war leaving in 1927 after 24 years service. He would receive a full pension after 22 years adult service, but had, of course, served two more years as a boy.